By Anu

In recent years, the conversation around the pro-Khalistan separatist movement seems to be growing louder, especially outside of India. I’ve noticed that some Gurudwaras in the UK (and beyond) are adopting different attitudes, and many Sikhs appear to be shifting their behaviour towards Hindus, which is understandably unsettling for many in both the Hindu and Sikh communities.

Personally, I feel disturbed when I see Khalistani flags during Nagar Kirtans or displayed at Gurudwaras. This feeling stems from the way I’ve always viewed Sikhs, which has been strongly influenced by the positive experiences and relationships I had during my childhood.

Early years in Punjab

When I look back on my early years in Punjab (India), I remember as a 12-year-old, starting high school. We were finally in the “big leagues” — new subjects, thicker books, and a whole world of opportunities opening up. School life was more than just lessons; it was about joining sports teams, learning musical instruments, and stepping into parts of the school we were never allowed to enter when we were younger. But even amidst the excitement of new beginnings, there was an undercurrent of unrest, far from our everyday thoughts.

There were whispers about terrorists — “ugrawadis” or “khaadkus” as we called them in Punjab. They were causing trouble in distant corners of the state. Every so often, curfews would be declared, sometimes for an hour or so a day, sometimes for a day or two and sometimes even longer, and we couldn’t go to school. Oddly enough, we found ourselves torn — sometimes enjoying the break, but other times, missing the rhythm of school life when these curfews lasted too long.

This was in a time before social media before the constant stream of information we have today. Television was a luxury, only a few houses had a set, and enjoying Sunday movie nights in a household that had a TV was a big deal. News was limited to Doordarshan — the state-run channel — and newspapers came irregularly, so our knowledge and understanding of the world was limited. We heard that pro-Khalistani terrorists (the media called them “Sikh terrorists”) were demanding a separate Punjab, but with little information, it all seemed distant, almost abstract.

Hindus and Sikhs lived in harmony

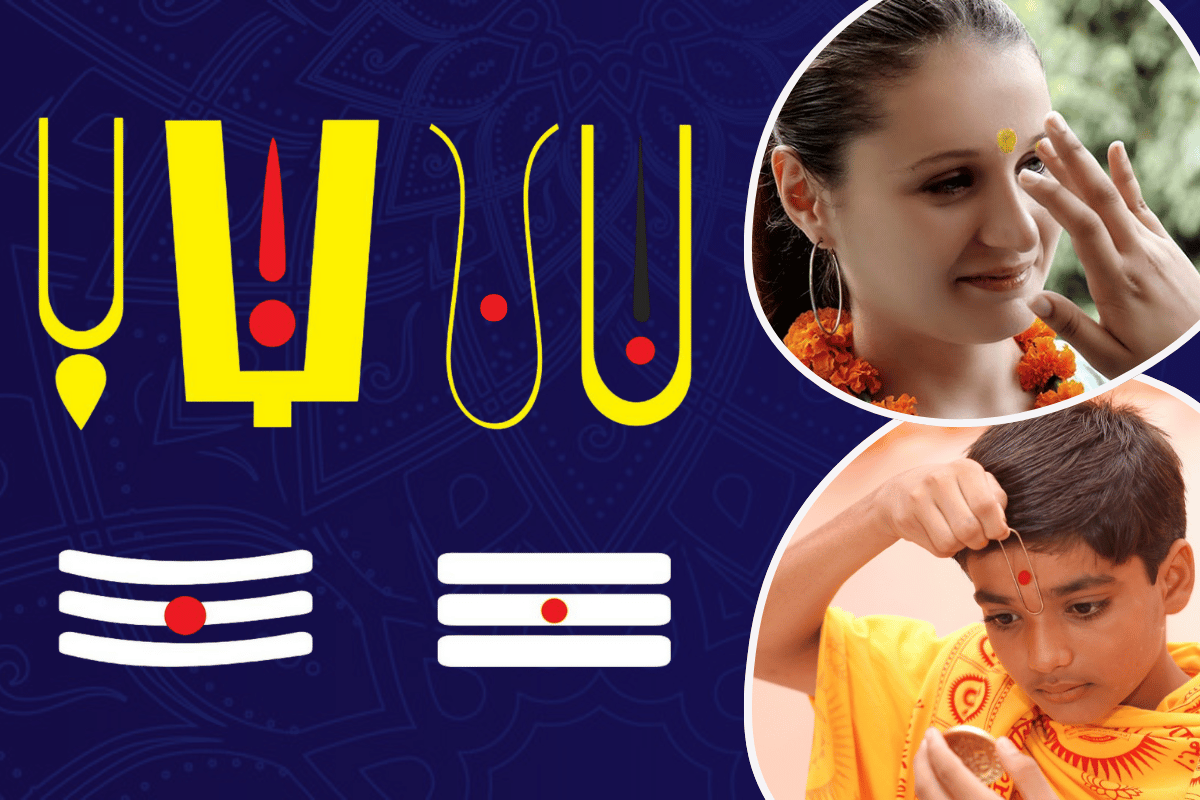

Our community, however, was quite peaceful and in harmony. We lived in a mixed neighbourhood, where Hindus and Sikhs had always lived side by side. One family, in particular, had four sons — three were Keshdharis (followers of Sikh traditions, sporting turbans and the Kara) and the youngest was Mona (following Hindu traditions to cut his hair). Their family had always maintained this delicate balance of tradition of donating their older sons to Gurus to become Singhs or Sikhs who will fight for the Dharma and keeping the youngest one for themselves as a Hindu. There was never a sense of division among us. Every morning, at 4 AM, we would wake to the sound of ‘Baani’ from the nearby Gurudwara. We’d wake up, get ready and walk with my Grandad to the dairy for milk and yoghurt, then head home to perform Aarti, before setting off for school.

There was never any thought about whether someone was Hindu or Sikh. We’d gather with our friends on the way to school, eager to reach early so we could play before the bell rang. In our school on Mondays, we’d sing Shabads from Gurbaani; on other days, we’d sing bhajans, and every first day of the month, we’d gather for a “havan”. None of us cared about who was singing what — it was about the fun of competing to be the loudest, especially when our teachers looked our way.

It wasn’t until much later that we began to understand what was happening outside our bubble. There were rumours about my board exams for year 8 in 1984 being cancelled due to the escalating violence. We couldn’t leave the house, and with no landline and no TV, we were disconnected from the outside world. But then, we began to hear horrifying reports — terrorists were pulling Hindus off buses and killing them. There were bomb blasts in some Hindu-majority areas and temples. People were scared to step outside but for us, it was still happening somewhere far, as we didn’t experience any of that in our area.

Terrorist attack

However, the peace in our area didn’t last that long. One night, I’ll never forget, we were all asleep on the roof during summertime, when suddenly we heard frantic shouts: “Water! Water!” We rushed to the edge of the roof and saw flames raging on the main road outside our house. My dad and the other men from the street sprang into action, hauling buckets of water to douse the flames. The fire started touching openly hanging street electric wires. People couldn’t use water anymore. The Sikh family I mentioned earlier had some sand as they were getting building work done so they used that sand to stop the fire from getting to the electric wires. We later found out it was a terrorist attack, a result of the growing violence when Police came to our street to take statements from people. Luckily, no one was hurt in this incident.

Despite all this, we didn’t feel any differently toward our Sikh neighbours or friends. Then, one day, the news came that Bhindranwala, the leader of the militant separatist movement, was hiding in the Golden Temple. The sacred Gurudwara was turned into a fortress, and many, both Hindus and Sikhs, were distressed by how it tarnished the sanctity of the place. The Indian government eventually sent forces to flush him out in what was known as Operation Blue Star, and Bhindranwala was killed.

Indira Gandhi assassinated

We thought the violence would end with him, but we couldn’t have been more wrong. Soon after, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated, plunging the entire region of Punjab and Delhi into chaos. Unrest gripped the area, and fear settled over our community. It was during this time that my father started a new business, buying two vans to rent out. We were excited, but that excitement was quickly shattered one night when we heard a loud crash. My dad rushed outside to find the windows of both vans smashed. I could see the distress on his face as he tried to reassure us that it wasn’t so bad, but the fear in his voice told a different story.

This did not finish in 1984. Things kept getting worse, a few years later when I was in college in 1992, one morning I went to one of my friend’s (who was a Sikh) house to get some notes at about 7.30 am and I knocked on the door a few times. It was expected that everyone would be at home at that time. They took ages to open the door and then eventually her mum came out and I heard her saying to her husband, “Come out, this is just our daughter’s friend.” My friend’s dad came out saying, “I thought that they had come here searching for him, he should stay in the village.” There was some relief on their faces, but I got the idea that someone in their family was under suspicion of terrorist activities. I never mentioned this to my friend that I understood why it took so long for them to open the door and we still remained friends. After a few days, she told me that it was her far cousin, he got killed in a police encounter and her whole family felt relaxed and they had broken ties with the activist family.

Hindus and Sikhs remain united

Through all of this, though, one thing remained constant: the bond we shared with our Sikh friends and neighbours. In school, in college, even now, I have Sikh friends who are like family. Even after the violence, I never felt a divide between us. In fact, several of my cousins and nephews have married into Sikh families, and I am unable to wrap my mind around the idea that some people want to tear apart such deep, familial connections. How could anyone separate the bloodlines, the hearts, and the shared traditions we had grown up with?

For me, this whole idea of separatism doesn’t make sense. How could anyone, especially someone you’ve grown up with, justify the actions of those who were so willing to divide and destroy? I still don’t understand it. But as I look back on those days, I’m reminded of the one truth that stood tall amid the chaos: no matter what was happening outside, the ties between us, Hindu and Sikh alike, could never be broken. And so, I just pray that these people who are trying to separate the community get in their heads that we are inseparable and somehow things get back to how it was when we were young, one and together.

Note: The word Sikh was mentioned by some news agencies to further the narrative that Sikhs were behind this movement. However many outside agencies were involved in fomenting trouble and the violence in the state had nothing to do with the average Sikh. The vast majority of Khalistanis were of Sikh-Jatt background, however, most Jatts were against the movement.