There was a time when Bhārat (India) was known as “Sone ki Chidiya (the Golden Sparrow)” for its unmatched prosperity, advanced knowledge and cultural richness. The phrase symbolised both its material prosperity and cultural richness; also, the Gurukul system of education was indeed a contributing factor.

Ancient Bhārat contributed a significant share of global GDP, according to economist Angus Maddison’s research (The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective, OECD, 2001), India accounted for around 32% of the world’s GDP in the 1st century CE and remained the largest economy until the 18th century.A key contributor to this success was the Gurukul system of education, which produced individuals with holistic knowledge in mathematics, science, medicine, governance, arts, and ethics. Rooted in Vedic principles such as collective learning (Rigveda 10.191.2) and moral duty (dharma), the Gurukul system ensured that knowledge was tied to social responsibility and economic productivity, sustaining Bharat’s golden era for millennia.

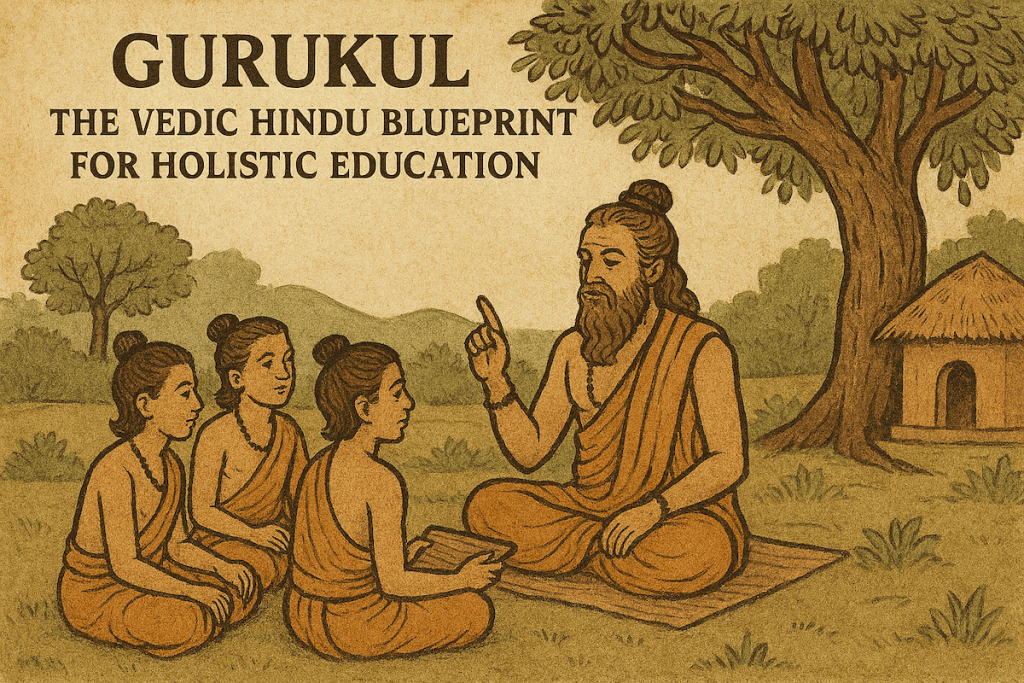

Gurukul

The term Gurukul comes from Guru (one who removes darkness), which can be loosely translated as teacher and kul, meaning extended family or home. All śiśyas (disciples) leave behind their parental dwellings, and enter the sanctum of the Guru’s household and dwell therein in body, mind and spirit for the entire duration of their learning.

The Gurukul system of education flourished in Bhārat during the Vedic Age. Bhagwān Rāma, Bhagwān Kṛṣṇa, the Pāṇdavas, the Kauravas and Prahlād et.al., were among its distinguished alumni. Despite belonging to royal and affluent families, they studied alongside less privileged disciples, with no discrimination based on economic or social background. Learning in such a diverse and inclusive environment nurtured empathy, mutual respect, and understanding, instilling life lessons essential for a meaningful and successful journey ahead. Therefore, the modern DEI wasn’t a thought exercise or an HR directive, it was inclusivity in action and conduct.

The Gurukul system is known for its emphasis on individual attention, discipline, and a combination of academic and extracurricular activities.

Life in the Gurukul

The Gurukul is an ancient residential system of education in Bhārat in which śiṣyas (disciples) reside in the home of the guru which allows them to learn from Guru’s example of conduct and values. The guru is far more than an instructor, he is a moral exemplar and a spiritual guide who bore the divine responsibility of imparting knowledge. Such knowledge while also shapes the disciple’s character, values and personality. In doing so, the guru transforms the śiṣya into a responsible and contributing member of society. Described as an affectionate father, an effective teacher and a person of high moral and spiritual calibre, the guru, maintains discipline not through coercion, but through the sheer influence of his character and example.

Rooted in the guru–śiṣya paramparā (teacher–disciple tradition), this model holds a sacred place in the cultural and spiritual heritage of Sanātana Dharma. The guru- śiṣya relation is built on mutual respect, trust and experiential learning.

Within the Gurukul system, śiṣyas (disciples) adhere to a disciplined and austere lifestyle that formed an essential part of their education. They are prohibited from consuming meat, sweets and strong spices, and are required to observe celibacy as a means of fostering self-control and purity of thought. This self-restraint at a young age allowed the individuals to flourish as well-rounded citizens rather than cogs in a society bent on consumerism/materialism. The GDP figures mentioned above are a testimony to these invaluable seeds sown at a young age. Daily routines begin bramha muhūrta , between 3:30 – 4 am with personal discipline, reverence toward the guru and elders, and strict adherence to prescribed rules of conduct. A distinctive feature of this system was the practice of bhīkṣā (alms-seeking), wherein śiṣyas collect food by begging from nearby households, not out of necessity, but as a spiritual exercise to cultivate humility and gratitude (Sharma, 2006). Guided by the ideal of “Plain Living and High Thinking,” the Gurukul ethos sought to nurture a sense of social responsibility and indebtedness to the community that supported the student’s education.

The Subjects taught and the curriculum and the teaching methodology

Different subjects are taught in the Gurukuls, and include the Vedas (also known as Śrutī) and the Vedāṅgas, the Āraṇyaka, the Ṣaḍdarśana (6 philosophies), the Brahmaṇas, Upniṣads, astronomy, astrology, language and grammar, fine arts, medicine, political science, economics, philosophy, theology, martial arts, archery, science, mathematics, defence studies and physical sciences.

Although the ultimate aim of education in the Gurukul system is the holistic development of the śiṣya, encompassing intellectual, moral, religious, and spiritual growth, it also sought to prepare students for various professions and meaningful service to society. The system’s core objectives include cultivating self-control, fostering strong character, promoting social awareness, enhancing personality and intellectual capabilities, deepening spiritual understanding, and preserving the vast repository of knowledge and cultural heritage passed down through generations. In this way, Gurukul education is not only a means of personal transformation but also a foundation for sustaining the social and cultural fabric of the Indic civilisation.

The Gurukul system place unwavering emphasis on nurturing in each śiṣya the inner strengths and virtues that would sustain him through all challenges of life, be it adversity or kingship. Instruction is personalised, allowing every disciple to advance at a pace suited to his capacity, as discerned by the guru (Atharvaveda 19.71.1). Continued acceptance within the Gurukul was contingent upon the śiṣya’s ability to uphold steadfast discipline, exemplary conduct, and unassailable moral integrity, virtues extolled in the Yajurveda (34.5) as essential to righteous living.

In the Gurukul system, Sanskrit was the principal medium of instruction, granting students direct access to the Vedic scriptures, and other classical texts in their original form, thereby safeguarding both linguistic sanctity and cultural heritage. Revered as a divya bhāṣā (divine language), Sanskrit is praised in the Rigveda (10.71.2) as the medium through which wisdom is preserved and transmitted across generations.

Ethics and values play a major role in everything that is done during the learning period, and students were taught to respect all living beings. The systems recognised the importance of knowledge in human spiritual progress, and education was considered a means of achieving spiritual enlightenment. The disciples were selected based on their impeccable conduct and greater strength.

During the Vedic period, the art of writing was less in use. A guru would usually recite the hymns of the Vedas, and his śiṣyas would recite the same in chorus. The entire instruction was orally given. Memorisation, recitation, and recapitulation were the normal methods of education.

Disciples were taught through an engaging blend of group discussions, self-directed study, and the acquisition of practical skills. Equal emphasis was placed upon the physical, spiritual, and cultural refinement of the śiṣya, nurtured through pursuits such as sports, yoga, meditation, and the arts. These endeavours, woven seamlessly into daily life, fostered holistic growth, shaping disciples into well-rounded individuals endowed with balance, discipline, and inner harmony.

The disappearance of the Gurukul System

The Gurukul system did not disappear overnight; rather, it declined gradually over several centuries.

- Late Ancient to Early Medieval Period (7th–12th century CE) – Gurukuls coexisted with large universities like Nalanda, Takshashila, and Vikramashila, but the emphasis began shifting toward these organised centres of learning. However, village and temple-based gurukuls still thrived.

- Medieval Period (12th–16th century CE) – Following the Islamic conquests and establishment of the Delhi Sultanate, Persian and Arabic madrasas became prominent in state-sponsored education, especially for administrative and scholarly roles in the court. Gurukuls continued but lost patronage in many regions.

- Mughal Period (16th–18th century CE) – While some Hindu rulers and communities preserved the Gurukul tradition, state focus remained on Persian-based education. Gurukuls increasingly relied on local community support rather than royal funding.

- Colonial Period (18th–19th century CE) – The most significant decline came under British colonial rule, especially after Lord Macaulay’s Minute on Education (1835), which promoted English-based education for administrative purposes. Traditional Gurukuls were sidelined in favour of Western curricula, funding was diverted, and Sanskrit-based learning was deemed less “practical” for government jobs.

By the late 19th to early 20th century, the Gurukul system existed mainly in isolated rural areas or through revivalist efforts (e.g., Dayananda Saraswati’s Gurukul Kangri in 1902), but as a mainstream model, it had effectively ceased to be the primary mode of education.

Conclusion

The education was completely free, and when the guru indicated that the śiṣya was ready to leave, śiṣya would offer the guru dakṣiṇā before leaving the Gurūkula. The guru dakṣiṇā is a traditional gesture of acknowledgement, respect and thanks to the guru, which may be monetary, but also may be a special task the teacher wants to accomplish.

In Bhārat, learning was a sacred duty, prized and pursued not as an accumulation of theoretical knowledge, but as a means of self-realisation, and Gurukul were one of the platforms through which this unique concept of education was disseminated.

The Gurukul system is renowned for its focus on personalised instruction, strict discipline, and a harmonious integration of academic learning with physical, artistic, and cultural pursuits. The Rigveda (10.191.2) emphasises the spirit of collective yet individualised learning, urging students and teachers to “learn together and share knowledge.” Discipline (niyama) formed the ethical backbone of this system, as reflected in the Yajurveda (34.5), which likens the guru’s role in shaping the student’s life to the sun illuminating the world. Education in the Gurukul extended beyond scholarly subjects to include music, archery, debating, athletics, and crafts, ensuring the all-round development of the śiṣya (Atharvaveda 19.71.1). This holistic approach prepared students not only for intellectual excellence but also for moral integrity, social responsibility, and physical vitality.

References

- Altekar, A. S. (1934). Education in Ancient India. Banaras Hindu University.

- Mukherjee, R. K. (1964). Ancient Indian Education: Brahmanical and Buddhist. Motilal Banarsidass.

- Sharma, R. N. (2006). History of Education in India. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors.

- Selvamani, P (2019). Gurkul System – An Ancient Educational System of India. International Journal of Applied Social Science. Vol 6 (6), June 2019