The Goa Inquisition represents one of the most traumatic and under-explored chapters in the history of Bhārat (India). Spanning several centuries under Portuguese colonial rule, this period was plagued by massacres, religious persecution, forced conversions, and the systematic suppression of Hindu culture in Goa. Despite its magnitude, the Goa Inquisition has not received much attention in mainstream historical studies or educational curricula. (Dr Vinay Nalwa, 2023)

This essay aims to raise awareness of the suffering endured by Konkani Hindus during this period and to highlight its continuing impact on the Konkani Hindu community today. Understanding this history not only sheds light on the challenges faced by the Konkani population but also provides valuable insights into the present-day struggles of marginalised Hindu communities in regions such as Pakistan, Kashmir, and Bangladesh. The phrase, “History repeats itself”, could never be unfortunately true, in the instances of Hindu persecution or genocide. The objective of this thesis/study is to focus on the Goa Inquisition chapter.

Historical background

The Portuguese arrived in Goa, India in the early 16th century, initially with the assistance of sections of the local Konkani Hindu population. At the time, the region was under the rule of Ibrahim Adil Shah of the Bijapur Sultanate, whose oppressive policies had created discontent among the local population. The Portuguese invasion targeted parts of modern-day Goa, particularly the talukas of Salcette (Sashashti), Bardez, and select islands, representing roughly one-eighth of the present-day territory. (Priolkar, 1992)

What followed was the imposition of the Inquisition, one of the most severe instruments of colonial and religious control. The Inquisition’s primary objectives were the suppression of Hinduism and the promotion of Christianity through missionaries. This was enforced through acts of violence, destruction of temples, confiscation of properties, and severe punishments against those who resisted conversion. (Priolkar, 1992)

Demographic and cultural impact

Before the arrival of the Portuguese, Hindus constituted an overwhelming majority of Goa’s population, estimated at between 90–99% during the 16th century. Over the course of the Inquisition and subsequent colonial policies, this demographic drastically changed. By the early 20th century, the Hindu population of Goa had been reduced to less than 15%. (Dr Vinay Nalwa, 2023) (The Catholic Encyclopedia: Fathers-Gregory, 1909)

This decline was not only the result of forced conversions and massacres but also mass displacement. Large sections of the Konkani Hindu community fled to neighbouring regions, including present-day Maharashtra, Karnataka, Kerala, and Gujarat. The dispersal of these populations contributed to the fragmentation of Konkani cultural identity, with many families losing direct ties to their ancestral lands. (Sangam Talks, 2018)

The cultural consequences were profound. Centuries of suppression resulted in the erosion of indigenous practices, rituals, and linguistic traditions. Many Konkani Hindus continue to grapple with this loss of identity, which has contributed to social and cultural challenges within the community today.

Ancient settlement and legendary origins

In the Skanda Purana, a historical Hindu text, the Konkan region, including what is now Goa, was reclaimed by the Hindu warrior-sage Parashurama, in a story which says he shot an arrow into the sea. The land that emerged became Gomantak, regarded as the cradle of Goan civilisation (Sangam Talks, 2018).

In historical and oral tradition, 108 Gaud Sarasvat families migrated and settled here around 1000 BC, fleeing the drought caused by the river Sarasvati drying up. They were divided into two groups:

- Tiswadi: settled by approximately 30 families (the name deriving from “30 villages”).

- Sasashti: settled by approximately 66 families (“66 villages”), renamed to Salcette under Portuguese rule.

- Bārdez: settled by approximately 12 families, thus the name deriving from “12 villages”.

These clan-based settlements laid foundational social structures still referenced today. (Nicolau, 1878)

Community Governance: Gaunkaris (Gaonkaris) and Communidades Life in these regions, especially in Salcete, Bardez, and Tiswadi, revolved around a village-based governance system, called the Gaunkar system, where land and resources were managed communally. The original settlers and their male descendants held rights through associations known as gaunkaris, later formalised by the Portuguese as comunidades. (Priolkar, 1992)

Historical polities and rule

Tiswadi and the surrounding territories frequently alternated between regional powers. Prior to Portuguese arrival, the area saw shifting control between the Bahmani Sultanate, the Vijayanagara Empire, and eventually the Bijapur Sultanate of the Adil Shahi dynasty in the 15th century. Under the Bijapur Sultanate, Goa, including Tiswadi, served as a regional capital. Despite Muslim rule and temple desecrations, traditional social structures like the gaunkari continued to function to some extent. (Dr Vinay Nalwa, 2023)

Agricultural specialisations and economy

All three regions, Bārdez, Tiswadi, and Salcete, were known for salt production, leveraging their estuarine geography (estuaries of the Mandovi, Zuari, Chapora, Terekhol, and Sal rivers). Salt farming was a vital economic activity, likely dating back centuries. In addition, the khazan system, a traditional method of coastal land reclamation and rice-fish agriculture using bunds and sluice gates was practised prominently in Bārdez. This system originated at least as early as the 5th–6th century and reflects the enduring ingenuity in managing Goa’s unique wetlands (Dr Vinay Nalwa, 2023)

Invasion and early Inquisition

Background and local collaboration

In 1510, the Portuguese, under the military leadership of Afonso de Albuquerque, seized control of Goa from the Sultanate of Bijapur with crucial assistance from Timoja, a local privateer and leader who had long resisted Bijapur’s rule. Timoji guided Albuquerque to believe that Goa would be easy to capture because of its weakened defences and internal strife. Albuquerque initially captured Goa, withdrew due to instability, and then returned in November 1510 with reinforcements to successfully take control by December. Around 6,000 of the 9,000 defenders perished in the assault. Albuquerque’s success earned him praise and allowed him to consolidate power in the region. (Dellon, Amiel and Lima, 1997)

The Initial Period: Relative atability and subtle Conversions

Following the conquest, Albuquerque maintained a relatively moderate stance toward indigenous communities. While conversions began in the early 1500s, they were limited and discreet, partly to sustain trade relationships and harmony with the local Hindu merchant class. This way, there would be social and economic stability in the region, which was essential for its prosperity. (Sushil Chaudhury, Morineau and France, 1999)

The arrival of Francis Xavier and his appeal for the Inquisition

Francis Xavier, the Jesuit missionary active across Portuguese India, broadened his missionary efforts to Goa in the early 1540s. He observed a marked return to pre-Christian practices among new converts and saw this as a threat to the permanence of their conversions. (Dellon, Amiel and Lima, 1997)

In 1546, Xavier penned a letter to King John III of Portugal, urging the institution of the Holy Inquisition in India. He framed it as essential for ensuring converts remained steadfast within Christianity and called for punitive measures for failing governors. (Sushil Chaudhury, Morineau and France, 1999)

Religious hardening and institutionalisation

Although Xavier’s recommendation was made in 1546, the formal Goa Inquisition only began officially around 1560, well after his death in 1552. Its legal framework was solidified by 1567, under the regency of Queen Catherine and under the influence of clerics such as Cardinal Henrique. (Teotonio R De Souza, 1990)

Accounts suggest there was already a religious push from figures such as Miguel Vaz, who advocated for the destruction of all Hindu temples in Goa by 1546, under the guise of religious purification. Thus began the period of ethnic cleansing. (Sangam Talks, 2018)

The massacres

Throughout this dark period, there were many villages which had been burned down, destroyed, massacred, and even had people kidnapped from.

Temple suppression and religious persecution (1566)

In 1566, the Portuguese government issued an unjust law banning the construction of new Hindu temples and the restoration of existing ones. The law further prohibited the creation of murtis (sacred idols), and imposed imprisonment on violators, while rewarding informants, a broad and ambiguously defined policy that invited widespread abuse and targeting of Hindus. This was also used as a tactic to divide the Hindu population through repeated acts of betrayal. (Dr Vinay Nalwa, 2023)

That same year, the Mangeshi Temple, one of the most prominent Mandirs, was demolished to make way for a Christian church. Yet, local devotees preserved the deity’s image (murti), securing a continuity of worship outside Portuguese-controlled domains. (Sangam Talks, 2018)

The Kunkulam massacre (circa 1583)

In 1583, Portuguese forces attempted to raze the Shantadurga Temple dedicated to the village goddess (Gramadevi) in Kunkulam, now known as “Cuncolim” (Portuguese influence). The villagers resisted fiercely and momentarily expelled the Portuguese. However, after agreeing to a truce, they were betrayed, the local chieftains were locked inside a building, and the entire village was burned alive, refusing mercy to all but one survivor, who escaped by fleeing downstream toward Karnataka (via a river), preserving the harrowing tale. There are many such stories in many other villages; however, this is the only documented massacre that remains. Many documents of other villages facing similar situations have been destroyed, and their stories have not been heard. We know that these stories do exist because of the number of Konkani Hindus that got expelled to other parts of the West coast. Currently, most Hindus who speak Konkani do not come from Goa, but rather neighbouring regions of the Indian West Coast. They can’t have all come from Kunkulam; there must have been many other villages. (Priolkar, 1992)

The Kunkulam revolt and retribution (1583)

That same year, in Kunkulam, the rebellion took a dramatic turn. When Jesuit priests and their Christian converts ventured into the village to establish a church, local gaonkars (village headmen) retaliated, killing five priests along with one Portuguese civilian and fourteen native Christians. (Priolkar, 1992)

In swift retaliation, the colonial authorities destroyed orchard fields and summoned sixteen chieftains under false pretences to the Fort of Assolna, where all were executed in cold blood, except one, who escaped to Karwar by jumping into the Sal River. Subsequently, the lands of the remaining villagers in Cuncolim, Velim, Assolna, Ambelim, and Veroda were confiscated and handed over to the Marquis of Fronteira. The temple of Shantadurga Kunkulikarian was relocated to nearby Fatorpa, and the site of the massacre later became home to the Church of Nossa Senhora de Saúde. (Priolkar, 1992)

Widespread temple demolitions and cultural erasure

Beyond these two tragedies, Portuguese authorities orchestrated a broader campaign of temple destruction. In Salcete, Diogo Rodrigues supervised the demolition of numerous temples, including those dedicated to Kamakshi, Ramnathi, Shantadurga, and Mangeshi and personally oversaw the annihilation of sacred spaces across multiple villages, with the stolen properties transferred to Christian institutions. (Sangam Talks, 2018)

According to compiled estimates, hundreds of temples were razed in Salcete and Bardez, with numbers reaching as high as 280 in Salcete and 300 in Bārdez, executed under the direction of Jesuits and Franciscans alike (Sangam Talks, 2018)

The unjust laws imposed

From the mid-16th century onward, the Portuguese Crown, working through colonial administrators, missionaries, and the Inquisition, institutionalised a series of anti-Hindu laws that systematically eroded the civil, social, and cultural rights of the indigenous population of Goa. These legal measures were intended not only to suppress Hindu religious practice but also to ensure political, economic, cultural, and social domination by the colonial authorities and the Catholic Church.

Restrictions on civil and political rights (Priolkar, 1992)

- Exclusion from Public Office: Non-Christians were forbidden from holding any public office. All civil, military, and administrative positions were reserved exclusively for Christians.

- Village Administration: Hindu clerks (kulkarnis) in village councils were replaced with Christians. Christian ganvkars (landholding freeholders) could make village decisions without Hindus present, whereas Hindus could not make political decisions unless all Christian members attended.

- Village Assemblies: In villages with a Christian majority, Hindus were forbidden from attending assemblies altogether. Even in mixed villages, Christian members were required to sign official proceedings first, relegating Hindus to a secondary status.

- Legal Inequality: In courts, Hindus were not accepted as valid witnesses. Testimony from Christians alone was admissible, automatically disadvantaging Hindus in all legal disputes.

Attacks on family and inheritance structures (Priolkar, 1992)

- Inheritance Manipulation: Hindu women who converted to Christianity were granted rights to inherit the full property of their parents, thereby creating both social incentives and family divisions.

- Custody of Children: Hindu orphans (which were defined as the father being dead whilst the mother was still alive) were automatically handed over to Jesuit Christian institutions for conversion and upbringing in Christianity. This legal measure effectively erased entire family lineages from the Hindu community.

- Marriage Restrictions: Hindu priests were forbidden from entering Portuguese-controlled Goa to officiate weddings. This was part of a deliberate attempt to weaken Hindu family law and force communities into dependence on colonial legal frameworks. Many people tried to get married by migrating outside of Goa.

Suppression of religious and cultural life (Sawani Shetye, 2022)

- Prohibition of Hindu Temples: A series of decrees forbade the construction of new Hindu temples and the repair of old ones. By 1569, a royal letter proudly recorded that all Hindu temples in Portuguese possessions in India had been demolished and burnt down (a decree known as desfeitos e queimados).

- Temple Demolition Squads: Missionaries, particularly the Jesuits, were charged with implementing these demolitions. Large-scale destruction occurred in Bārdez, Tiswadi, and Salcete, where virtually every pre-16th-century temple was razed.

- Ban on Ritual Objects: Hindus were forbidden from producing Christian devotional images or symbols, but at the same time, they were also prohibited from carving or creating Hindu murtis (idols). The vagueness of this law allowed the Portuguese to criminalise even household religious art.

- Expulsion of Priests: Hindu priests were systematically expelled from Portuguese territories, leaving communities without spiritual leadership.

Economic and social marginalisation

- Property Seizures: Hindu lands and estates were confiscated, often redistributed to newly converted Christians or church institutions. In many cases, prosperous Hindu families lost their agricultural and economic base overnight. (Panikkar, 1999)

- Restrictions on Professions: Hindus were barred from certain trades, particularly those involving sacred or symbolic crafts such as gold smithing, sculpture, and woodwork. This both destroyed traditional livelihoods and further reduced their cultural autonomy. (Panikkar, 1999)

- Discriminatory Taxation: Hindus were subjected to heavier taxes compared to Christians, reinforcing economic coercion as a method of pushing conversions. This was very similar to the jaziya law implemented by the Muslim Mughal rulers around the same time period. (Panikkar, 1999)

Social consequences and displacement

The cumulative effect of these laws created unbearable pressure on Hindu communities. Many sought refuge by fleeing across the rivers of Goa into territories ruled by Hindu or Muslim kings, particularly in present-day Karnataka and Maharashtra. This struggle for escape and survival is poignantly captured in the famous Konkani folk song “Haav Saiba Poltodi Vaita” (“O Lord, I am going across the river”), which reflects the desperation of those trying to cross the Zuari River to escape Christian persecution. (Manohararāya Saradesāya, 2000)

These discriminatory policies were not isolated legal oddities but rather part of a deliberate colonial strategy to dismantle Hindu society in Goa. Coupled with the Inquisition’s terror apparatus and repeated incidents of mass violence, including village burnings and forced displacements, collectively amounted to what many historians and descendants describe as cultural genocide. (Manohararāya Saradesāya, 2000)

Other forms of oppression and mechanisms associated with it

Coercive and deceptive methods of conversion

While violence was widespread, conversions also occurred through cunning and deceptive coercion. We can broadly categorise this as the contamination of food and water sources. There are accounts of Portuguese agents putting beef inside wells to convince Hindus that they have lost ritual purity and therefore must convert to Christianity. There are many other traditions which were manipulated for the same purpose. (De, 1989)

Suppression of language and cultural traditions

The Konkani language, the lifeline of local culture, was aggressively suppressed. In the late 17th century, decrees made speaking Konkani in public illegal, mandating Portuguese for administration and Latin for the Church. Attempts were made to cut off the population from its own oral traditions, folklore, and scriptural recitations.

Traditional clothing was similarly targeted. Hindu men and women were banned from wearing dhoti, sari, and kurta (the traditional clothing items), with European garments made compulsory. Even minor customs were monitored. For example, eating plain rice was linked with Hindu identity, whilst Christians were instead associated with “salty rice.” Hindus were sometimes force-fed salted rice as an act of humiliation and symbolic erasing of their identity. (De, 1989) (Panikkar, 1999)

Torture and the machinery of the Inquisition

The Goa Inquisition employed brutal methods to instil fear and ensure compliance. Commonly recorded tortures included:

- The pulley system, where victims were suspended and dropped to dislocate limbs.

- Waterboarding, simulating drowning to extract confessions.

- Burning with candles, especially in sensitive areas like the armpits.

- Psychological torture, including confinement and public humiliation. (Panikkar, 1999)

The most infamous punishment was the Auto da Fé (“Act of Faith”), a public spectacle where “heretics” and “apostates” were paraded before being burned alive. This punishment was often inflicted not only on practising Hindus but also on neo-converts accused of “backsliding” into Hindu customs. (Panikkar, 1999) (Sawani Shetye, 2022)

In Old Goa, there is a monument called Haatkatro Khamb, literally translating to “Hand-cutting pillar”. This was named that because in this period, one of the punishments was to tie “heretics” and “apostates” to the pillar. The Portuguese officials would then chop the accused’s hands off and leave them to bleed to death.

Targeting of women

Women were disproportionately vulnerable. Beyond forced conversions, they were subjected to sexual violence, mutilation, and enslavement. Records and oral histories indicate instances of women being trafficked to Portuguese colonies in Brazil, Mozambique, and East Africa, where they were sold into slavery or forced concubinage/marriage. They did this as an alternative to the practice of Sati, which they had banned to ‘reform’ Hindu practices. Some sources also allege that women endured genital mutilation as part of punitive practices, though such acts were rarely documented officially. (Panikkar, 1999) (Sawani Shetye, 2022)

Scale of atrocities

Despite Portuguese efforts to conceal the full extent of their crimes, many Inquisition records were deliberately destroyed after its abolition in 1812. Surviving documentation provides chilling statistics. Between 1560 and 1623, for a population of roughly 250,000-300,000, there were 16,712 recorded cases of torture and executions in Goa. The true number is likely much higher, due to concealment.

Lasting consequences

The combined effect of these laws and brutalities was catastrophic for Goa’s Hindu society:

- Mass migrations to territories under Hindu rulers in Karnataka and Maharashtra depopulated large parts of the “Old Conquests” (Tiswadi, Bardez, and Salcete).

- Loss of cultural identity, as Konkani was marginalised, Hindu customs were criminalised, and surviving traditions were forced underground.

- Social scars that persisted well into the 20th century, visible in the fragmentation of Konkani identity and the long struggle to reclaim temples and language.

The Impact on the Konkani population

Demographic shifts by the early 20th century

By the early 20th century, the demographic consequences of the prolonged Goa Inquisition were stark. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia of 1909, Christians accounted for approximately 80.33% of Goa’s population, with 293,628 out of 365,291 individuals identifying as Catholic. Before the Inquisition, the Christians represented an estimated 10-15% of the population, even after the subtle conversions. These overwhelming statistics reflect the centuries of forced conversions, oppression, and cultural upheaval, which decimated the Hindu presence in the territory. (The Catholic Encyclopedia: Fathers-Gregory, 1909)

Revival and transformation after liberation (Post-1961)

Goa’s annexation by India through Operation Vijay in 1961 marked a tremendous demographic reversal. By that time, a mass exodus of Catholic Goans had already begun, reducing their share significantly.

Subsequent censuses highlight the pace of change:

- 1960 (South Goa): Hindus comprised 51%, Christians were 47% — a narrow margin of roughly 14,000 individuals.

- 2011 (India): Hindus represented about 66.1% of the Goan population, Christians approximately 25.1%, and Muslims around 8.3%.

This demographic realignment was driven by two intertwined factors:

- Emigration of Christians, particularly to metropolitan Indian cities and overseas locations.

- In-migration of Hindus from other Indian states, reshaping the religious and cultural makeup of Goa.

Internal displacement of Konkani people

Large numbers of Hindus fled Goa during the Inquisition (16th–18th centuries), resettling in Maharashtra, Karnataka, Kerala, and Gujarat. Many of their descendants still live in these regions. These displaced groups carried their Konkani traditions, deities, and festivals, but being scattered across regions. Eventually, they adapted to local cultures. Over time, different dialects of Konkani emerged, influenced by Marathi, Kannada, Tulu, and Malayalam. This created a fragmented Konkani identity, where language and cultural practices varied depending on the region of refuge.

Language and cultural restoration

While not directly demographic, this period also saw a cultural reclamation:

- Konkani was granted official status in 1987 under the Goa, Daman and Diu Official Language Act, 26 years after liberation, which highlights a long-delayed revival of suppressed linguistic pride.

Today, many Konkani families, especially those who migrated centuries ago, speak Marathi, Kannada, or Malayalam instead of Konkani. This may be an indication that the language could go extinct within the coming decades.

Relevance today and learnings

Parallels with present-day marginalised Hindus

The Goa Inquisition is not merely a matter of the past. It continues to hold relevance for understanding present-day challenges faced by Hindu communities across the Indian subcontinent (South Asia). The patterns of persecution, forced displacement, and cultural suppression witnessed in Goa find disturbing parallels with the ongoing experiences of Hindus in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Kashmir, West Bengal and the North-Eastern states. The methods may differ in detail, but the underlying themes, such as the denial of religious freedom, destruction of cultural institutions, erosion of language, and demographic transformation, are disturbingly similar.

The impact of displacement

Despite the magnitude of the suffering endured during the Goan Inquisition, the broader Hindu community has often failed to integrate these lessons into its collective memory. This has resulted in a weak awareness of the mechanisms by which oppression takes root and how it can be resisted. Goa’s Hindu traditions, even today, continue to recover from the cultural trauma of centuries of suppression. The displacement of Konkani Hindus from their homeland severed them from their ancestral roots, and the Konkani language itself was severely weakened. In many diasporic Konkani communities, Marathi, Kannada, or Malayalam have become dominant, leaving Konkani struggling for survival despite ongoing revival efforts.

Key lessons Hindus must learn

The key lesson lies in recognising how easily cultural identity can be eroded when communities are fragmented and their languages and traditions suppressed. If urgent measures are not taken to protect vulnerable Hindu populations in regions such as Pakistan, Bangladesh, Kashmir, West Bengal, and the North Eastern states, history may, or rather will, repeat itself. Just as large sections of the Konkani Hindu population lost both their homeland and their cultural continuity, these communities too may face permanent displacement, assimilation, or extinction.

Thus, the Goa Inquisition serves as a reminder not only of the resilience of Hindu traditions but also of the cost of inaction. The safeguarding of language, rituals, and cultural identity must remain a priority if such histories are not to be repeated in new forms in the modern age.

Definitions

Historical Figures / Events

- Ibrahim Adil Shah – Ruler of the Bijapur Sultanate, known for persecuting Hindus.

- Afonso de Albuquerque – Portuguese general who conquered Goa in 1510.

- Francis Xavier – Jesuit Christian missionary active in Goa as well as other parts of the world, who played a role in calling for the Inquisition.

- Dom João III – King of Portugal during the early expansion of the Inquisition.

- Queen Catherine of Austria (Dowager Queen) – Regent of Portugal, who approved the Goa Inquisition under Cardinal Henrique’s influence.

- Cardinal Henrique – Influential cleric, key advocate for harsher Catholic policies. He spearheaded the Goa Inquisition implementation.

- Timmoja – Spy who aided the Portuguese in conquering Goa from Ibrahim Adil Shah.

- Operation Vijay – The Indian military operation in 1961 that ended Portuguese rule in Goa.

Religious / Cultural Terms

- Mandir – Hindu temple.

- Vigraha / Murti – Sacred idol or representation of a deity in Hinduism.

- Purohit – Hindu priest.

- Brahmins – Priest-scholar in Hindu society.

- Gramadevi/Gramadevata – Village goddess (e.g. Shantadurga, Vithoba).

- Gaonkar – Freeholder or member of a village community assembly in Goa.

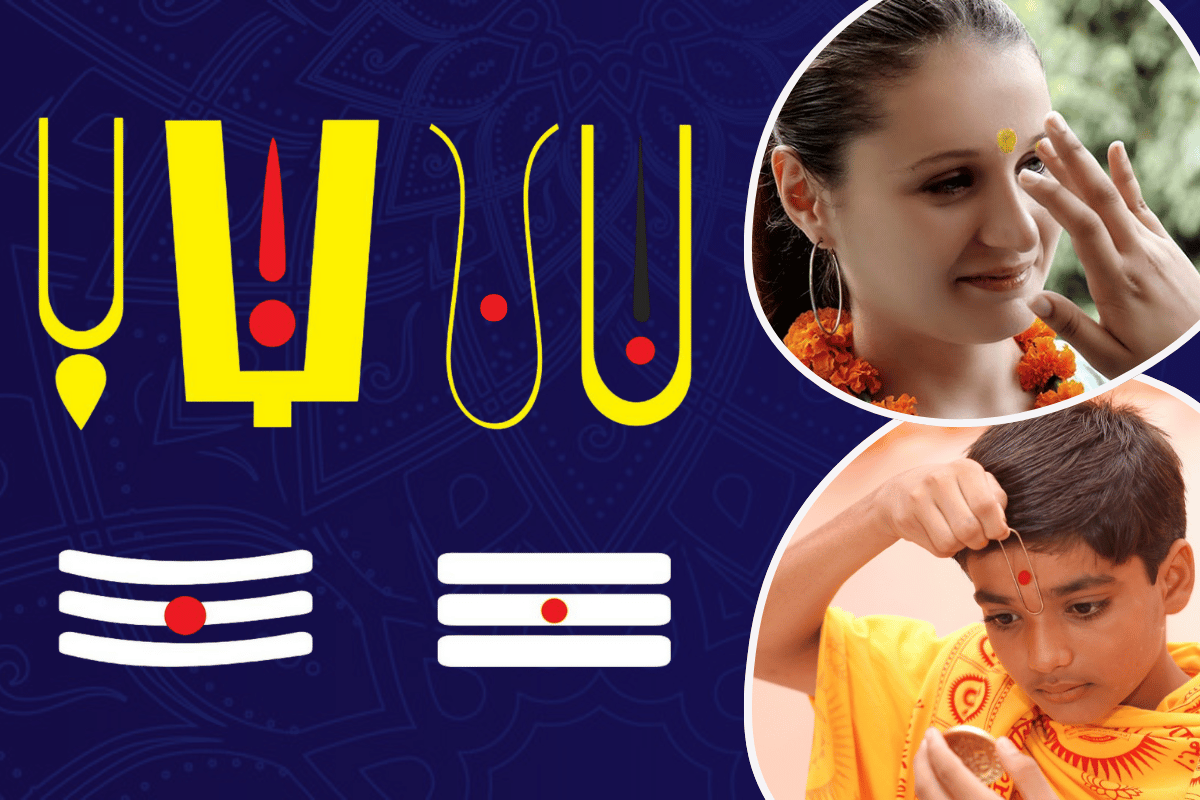

- Shikha (Shendi) – Sacred tuft of hair at the back of a Hindu male’s head, associated with ritual purity.

- Dhoti, Kurta, Sari – Traditional Indian clothing.

- Salty rice tradition – A symbolic ritual practice.

Places / Regions

- Sasashti/ Salcete – Taluka (administrative region) in South Goa.

- Bardez – Taluka in North Goa.

- Kunkulam – Village in Goa, site of the 1583 massacre.

- Western Ghats – Mountain range along India’s western coast.

- Konkan region – Coastal strip covering the states of Goa, Maharashtra and Karnataka.

Inquisition and Portuguese Terms

- Goa Inquisition – Ecclesiastical tribunal established by the Portuguese in 1560 to enforce Catholic orthodoxy and suppress Hindu practices.

- Auto da fé – Portuguese term meaning “act of faith”; public ritual where heretics were sentenced, often burned alive.

- Jesuits – a Catholic religious order that played a leading role in conversions and temple destruction.

- Proselytisation – Active attempt to convert people to another religion.

Atrocities and Laws

- Kunkulam Massacre – Incident in which the Portuguese locked villagers in a building and burned them alive (1583).

- Anti-Hindu laws – Set of discriminatory regulations (e.g., forbidding Hindus from holding office, testifying in court, building temples, or inheriting property).

- Temple demolition squad – Jesuit-led group tasked with destroying Hindu temples.

- FGM (Female Genital Mutilation) – A form of torture and bodily violation inflicted on women.

Folk / Cultural References

- “Haav Saiba Poltodi Voita” – Konkani folk song reflecting the hardships of Hindus attempting to flee Goa.

About the territory

Figure 1: Map of Portuguese Goa (red) marked within the current map of the Indian state of Goa (Wikimedia.org, 2009)

References

- Anant Kakba Priolkar (1992). The Goa Inquisition. (Priolkar, 1992)

- Dellon, G., Amiel, C. and Lima, A. (1997). L’Inquisition de Goa. Editions Chandeigne.

- Dr Vinay Nalwa (2023). Blood In The Sea: The Dark History Of Hindu Oppression In Goa. Prabhat Prakashan.

- The Catholic Encyclopedia: Fathers-Gregory. (1909).

- Teotonio R De Souza (1990). Goa through the ages. New Delhi: Concept Publ. (Teotonio R De Souza, 1990)

- Nicolau, J. (1878). An Historical and Archæological Sketch of the City of Goa. (Nicolau, 1878)

- Sushil Chaudhury, Morineau, M. and France, P. (1999). Merchants, companies, and trade: Europe and Asia in the early modern era. London ; New York: Cambridge University Press. (Sushil Chaudhury, Morineau and France, 1999)

- De, R. (1989). Essays in Goan History. Concept Publishing Company. (De, 1989)

- Manohararāya Saradesāya (2000). A history of Konkani literature : from 1500 to 1992. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. (Manohararāya Saradesāya, 2000)

- Panikkar, K.M. (1999). Asia and Western dominance. Mumbai: Somaiya Publications. (Panikkar, 1999)

- Borges, C.J. and Helmut Feldmann (1997). Goa and Portugal : their cultural links. New Delhi: Concept Pub. Co. (Borges and Helmut Feldmann, 1997)

- Sangam Talks (2018). Goa Inquisition : Lest We Forget | Shefali Vaidya | #SangamTalks. [online] YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6nEseljBZ-c [Accessed 24 Aug. 2025].

- Sawani Shetye. Dark History Of Goa | Archaeologist Sawani Shetye | The Ranveer Show हिंदी128. [online] YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nUxVTRWXf94 [Accessed 25 Aug. 2025]. (Sawani Shetye, 2022)

- Wikimedia.org. (2009). File:GoaConquistas.png – Wikimedia Commons. [online] Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GoaConquistas.png [Accessed 26 Aug. 2025]